Tina Medina was not a sickly child, yet she grew up knowing something was physically wrong.

She had difficulty keeping up with the other kids in her sixth-grade class and couldn’t run without becoming breathless. Local physicians near her home in Moriah, New York, shrugged it off as asthma — until Tina’s heart stopped twice during a routine appendectomy.

“I was told I had a severe heart condition and needed to see a cardiologist right away,” she says.

At 15, Tina was diagnosed with restrictive cardiomyopathy, a rare type of cardiomyopathy that causes the heart muscle to become stiff, making it difficult for the ventricles of the heart to properly fill with blood. Three years following her diagnosis, now a college freshman on her way to Syracuse University, she became severely ill with multiple episodes of congestive heart failure.

“The doctors I was seeing in Burlington referred me to Boston Children’s Hospital,” she says. “It was time to look at getting a transplant.”

Tina was listed for six months. She was in the cardiac intensive care unit at the University of Vermont Hospital in Burlington when she learned a heart had become available.

“I had no perspective that this was a danger, or that this was a huge deal. I looked at it as, I am finally going to be able to run, be able to breathe and not be sick.”

Boston Children’s nurse practitioner, Patricia O’Brien, CPNP, vividly remembers standing in her kitchen, telephone in hand, scrambling to arrange a flight from Burlington to Boston. “We had a plan in place but it fell through, so we were desperately trying to figure out a way to get her here, and we did.”

Tina’s surgery was performed on Aug. 27, 1992. She was the 22nd heart transplant patient at Boston Children’s, which performed its first cardiac transplant 30 years ago.

Looking back and moving forward

Dr. John Mayer, who still works at Boston Children’s as a senior associate in the Department of Cardiac Surgery, was Tina’s surgeon. He also happens to have performed the first heart transplant at Boston Children’s, back on May 16, 1986.

“We started the Heart Transplant Program to treat a group of patients for whom transplantation was their only therapeutic option,” says Mayer.

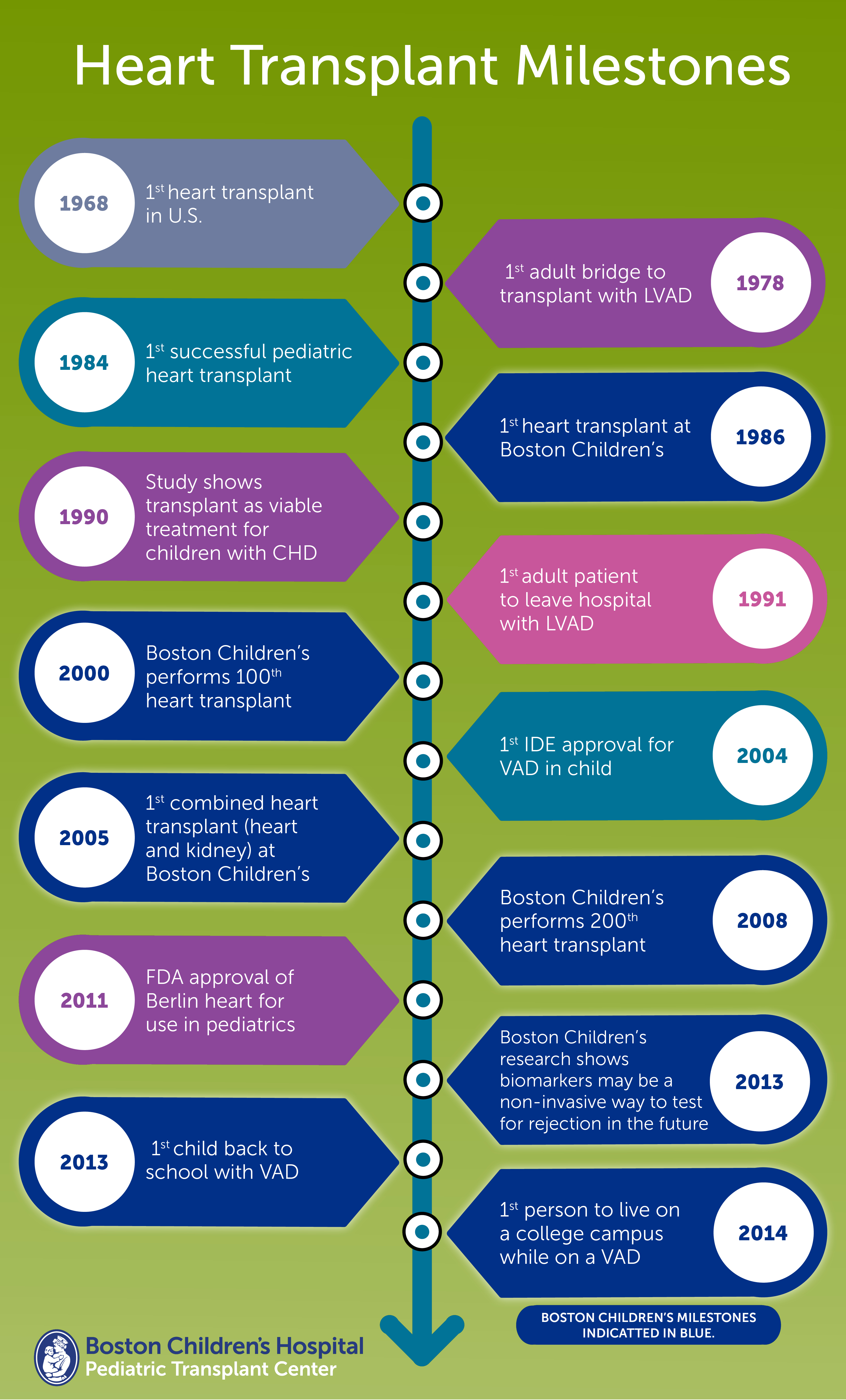

The first heart transplant in the U.S. was performed in 1968 at Stanford University School of Medicine. But it would be 16 years before a successful pediatric heart transplant would take place — June 9, 1984, at Columbia University Medical Center.

By that time, survival rates had improved, due in part to the introduction of a game-changing immunosuppressant drug called cyclosporine. “It all of a sudden meant drugs for immunosuppression were more effective and not as toxic,” Mayer says. “It fundamentally changed the paradigm.”

That first year, 1986, the team performed a total of three transplant surgeries. When Pat O’Brien joined the Department of Cardiac Surgery one year later as nurse practitioner for the post-operative surgery service, she also became the heart transplant coordinator, orchestrating everything from lab tests to travel, just like she did for Tina Medina.

“It was a fabulous experience,” Pat says. “I learned an enormous amount of medicine and became a better clinician because of my transplant experience. And the best part was working with the families, taking patients who are at death’s door and seeing them 20 years later and knowing you had a hand in it.”

By the late 80s, the Heart Transplant Program was performing six to eight transplants a year and had become what Pat called “a well-oiled machine.” Heart transplant was less of a novel procedure, the team was expanding and the protocols were becoming familiar to everyone. Mayer was making his mark by performing transplants other centers wouldn’t.

“There was conventional wisdom, supported by a few reports, that a transplant for a child with congenital heart disease (CHD) was far more challenging and higher risk,” Mayer says. “But we found unique ways of dealing with the distorted anatomy associated with CHD.”

Despite the progress over the years, one thing remains unchanged — the number of donors. “We’ve lost some patients because a heart wasn’t available in time,” says Mayer.

Mechanical circulatory assist devices, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and ventricular assist devices, have helped buy time, yet more than 4000 people in the U.S. are waiting for a heart transplant. “It’s a fact of the process,” says Kenny Laferriere, BSW, CTBS, a quality systems specialist at the New England Organ Bank (NEOB). “More people are becoming eligible for these life saving transplants, but the donor pool has only increased in small numbers throughout the years.”

Kenny is well versed in the world of transplant, not only because he works at NEOB, but also because he is a transplant recipient himself. He received his new heart 15 years ago. “Each day, I am humbled to be able to ‘pay it forward’ and help others get the transplants they so desperately need.”

She’s been here before

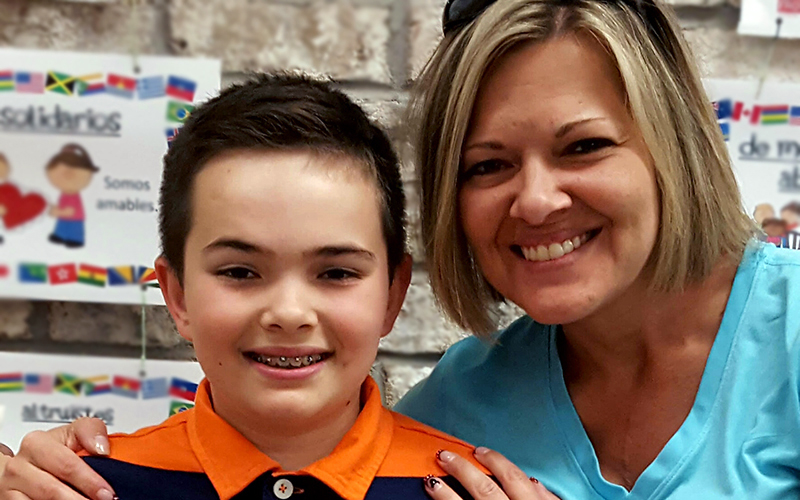

Twenty-four years later, Tina Medina, now married and a mom, still has the heart from her first and only transplant. She knows it has lasted longer than most.

What she didn’t know at the time of her transplant — or before she became pregnant — was that her condition had a genetic component. At age 7, her son Luke was diagnosed with restrictive cardiomyopathy. He’s under the care of Dr. Betsy Blume, medical director of the Heart Transplant Program, and will likely be listed for a transplant within a year or two.

“Things are so much different for him than when I was there — the technology, the immunosuppressant medication,” says Tina. “They know you will make it through the surgery. Now, it’s just whether you will get a heart and how the heart will hold up afterwards.”

Learn more about the Boston Children’s Heart Transplant Program.