by Emily Williams and Isis Rivera

After her first kidney transplant failed, Isis spent five years receiving tri-weekly dialysis. Then, in May, she got news she never expected.

Isis: Things fall apart…

In my mind, my childhood is distinctly split into two halves. I refer to them as the pre- and the post-implosion periods, describing my diagnosis as the implosion, in which my life collapsed in on itself. You see, I was not born with kidney disease. It wasn’t until I was about 11 years old that I was diagnosed with end-stage renal failure.

The pre-implosion period was marked by ridiculous and funny childhood-isms. It sounded like being scolded for eating sugar out of the jar and Jesse McCartney CDs. It felt like the adrenaline rush that came with sprinting home before the streetlights went on and the excitement of annual Scholastic Book Fairs. It looked like annual trips to the Frog Pond Spray Pool and window-shopping at the Prudential.

The post-implosion period, however, seemed like a different universe. It looked like perfectly-rectangular, fluorescently-lit rooms and needles. It sounded like a chorus of beeps, dings and hisses emitted by various machines and medical personnel grumbling unintelligible words to me. It felt like the constant chill of anemia and crippling isolation.

These two halves of my past have come to forge the strength and resilience that has allowed me to successfully navigate how to be a chronically-ill person. Together, the positive and negative parts of the last decade of life have given me the tenacity to push through a total of eight years of dialysis, a multitude of surgical procedures and the agonizing loss of my first kidney transplant.

By May of 2018, I had been in college for two years and had been receiving dialysis tri-weekly for about five years. I had accepted that maybe I just wasn’t meant to have the freedom that would come with a transplant. Maybe after losing my first transplant I didn’t get, or deserve, a second chance.

Emily: When grief becomes a gift

Much of my life has been defined by loss. That loss has taken many forms. Sometimes, it hurdles in with horrific force and other times it sneaks up silently. But it shares one common thread: It has been out of my control.

So, imagine how I felt when I realized that I do have the ability to control destiny, to offer hope to someone else.

When I first started working at Boston Children’s Hospital, I was asked to write for the Pediatric Transplant Center. I interviewed many families whose children had received organs from living donors: sometimes a family member, other times a friend or even a mere acquaintance. But no matter who it was, there was a central theme — gratitude — not just expressed by the recipient, but also the donor. The process of organ donation may have saved one life, but it had forever changed two.

I began to ask myself what was stopping me from doing the same. This past February, I began the evaluation process to donate a kidney at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where living donor surgeries take place for individuals donating to a patient at Boston Children’s.

Some friends and family members were supportive, others thought it was odd, and there were those who believed I’d gone mad — literally: “What if your other kidney fails?” “Aren’t you terrified of the surgery?” “Can I convince you to change your mind?” But anyone who knows me well knows once I make a decision, I relentlessly charge ahead. The truth is, I wasn’t worried at all. I wanted my life to have meaning. I wanted to channel the grief I’d experienced into something positive.

A few months later, my plan became a reality. On June 21, when I was wheeled into the operating room, I had no idea who would receive my kidney, but that didn’t matter. I was giving someone hope.

As it turns out, she gave me hope, too.

Isis: …and then things fall together

During one of my dialysis treatments, I was informed a stranger had come forward to donate their kidney to me — someone who was a near perfect match. I couldn’t help but spend the rest of that dialysis treatment — one of the last I would have — bawling tears of joy.

On June 20, I was admitted to the hospital to prep for my transplant on the following day. I did not know who my donor was, and I had so many questions. I knew I’d been through plenty of procedures and wasn’t afraid, but were they? Were they second-guessing their decision? Would they change their mind? Would I have to return to dialysis?

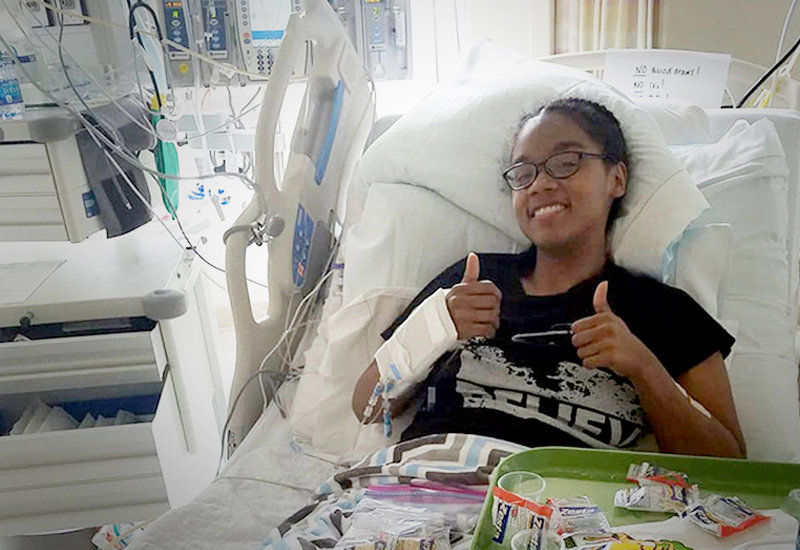

Twenty-four hours after my admission, I was back in my hospital bed with a fresh surgical scar. Three weeks later, I was back home, continuing my healing process. Three weeks after that, I met my altruistic donor, Emily. She was everything I thought she’d be. The energy she emanates lights up the entire room. Her excitement and passion for things makes you equally passionate and excited. Her generosity changed my life tremendously and gave me the sense of normalcy I desperately wanted but had given up on believing I’d ever achieve.

It is now four months after my initial meeting with Emily. Her kidney, or as I call it, “my bean,” is doing very well. In addition to taking the best care I can of Emily’s kidney, I’ve tried to spend a lot of my extra time advocating for organ transplants and reaching out to others with chronic illnesses in the hope of spreading the following two messages: You are not alone. And the actions of one person can be truly life altering.

Emily: A new home for my bean

In late summer, I met 20-year-old Isis Rivera, a junior at Simmons College and the recipient of my — as she calls it — “bean.” I am so lucky.

She’s smart, witty, kind and beautiful, both inside and out. She’s passionate about spreading the word about kidney health and organ donation. And she’s become my good friend. Boston Children’s renal transplant coordinator, Courtney Risely, put it best when she said, “Isis will take wonderful care of your kidney.”

I couldn’t have asked for a better home for my bean.