40% of pediatric transplant recipients have identifiable mutations

In adults, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is most commonly a complication of diabetes or hypertension. In children, teens and young adults, it’s a different picture. New research finds that more than half of people needing a kidney transplant before age 25 have a congenital anomaly of the kidney or urinary tract, and that 40 percent have an identifiable genetic cause of ESRD.

Knowing the genetic underpinnings of kidney disease can have important benefits for patients and their families, especially those with nephrotic syndrome, says study leader Friedhelm Hildebrandt, MD, chief of the Division of Nephrology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Hildebrandt and his colleagues drew on 263 families whose child received a new kidney at Boston Children’s between 2007 and 2017, before the age of 25. In 68 families, the team was able to perform whole-exome DNA sequencing, comparing the “spelling” of each gene that encodes for a protein with a normal reference sample.

The genetics of ESRD

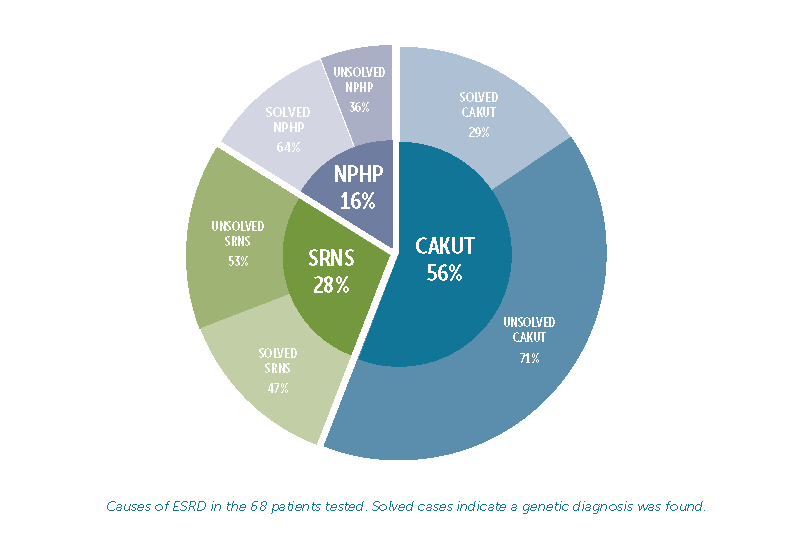

To date, mutations in about 240 different genes have been linked to ESRD. In the study, DNA sequencing found a causative mutation in 27 of the 68 patients tested (39.7 percent). Results varied among the different causes of ESRD:

- Congenital anomalies of the kidney or urinary tract (CAKUT) were the leading cause of ESRD, affecting 56 percent of patients. Of these, DNA testing provided a genetic explanation for 29 percent of families.

- Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) was the cause of ESRD in 28 percent of patients, and 47 percent of families received a genetic diagnosis.

- Nephronophthisis (NPHP), the third leading cause of ESRD, affected 16 percent of patients, and 64percent of these families received a genetic diagnosis.

Whole-exome sequencing: Benefits to children with ESRD and their families

Having a genetic explanation for ESRD allows families to receive counseling and possibly have other family members tested, says Dr. Hildebrandt, who is also the William E. Harmon Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. Just as important, some genetic causes of kidney failure can have effects beyond the kidneys, such as eye or liver disease, heart defects or hearing loss. Knowing the genetic cause allows children to be screened for these problems and treated as necessary.

Whole-exome sequencing can have value even after a transplant, notes Dr. Hildebrandt.

“Some genetic disorders causing ESRD could have other symptoms that adversely influence the course of disease, but can be treated,” he says.

One example is primary hyperoxaluria, in which excess amounts of oxalate are stored in non-renal tissue. This oxalate could be released after a transplant and harm the transplanted kidney, so it’s important to diagnose primary hyperoxaluria at any time point.

For children with SNRS and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), the most severe form of nephrotic syndrome, DNA sequencing results may offer reassurance. People with FSGS often have disease recur in the transplanted kidney — but in the study, no patient with a genetic diagnosis had such a recurrence.

“The genetic disease is intrinsic to the kidneys of the transplant recipient and not the donor’s,” Dr. Hildebrandt explains.

A genetic diagnosis can also help in tailoring pre- and post-transplant treatments for SNRS. For example, children might need a customized immunosuppression regimen if their genetic findings predict that FSGS will not recur, or predict that they will encounter specific side effects from steroids.

“We think whole-exome sequencing should be considered in all patients under 25 with ESRD the moment they are diagnosed with chronic kidney disease,” says Dr. Hildebrandt.

Evaluating kidney donors

Genetic findings can also have implications for potential living donors.

“Some relatives who wish to be evaluated as donors may be at a higher risk for ESRD themselves, so may not be ideal donors,” says Dr. Hildebrandt. “Knowing the genetic cause allows us to test potential donors for the same gene.”

Indeed, when the research team tested family members in a related study, they found disease-causing mutations in 16 percent of families with CAKUT, 60 percent of families with SNRS and 64 percent of families with NPHP.

Research on the genetics of ESRD is ongoing. Boston Children’s continues to enroll children and young adults from around the world, including those with kidney transplants.

“Understanding the genetic basis of a child’s disease may have an important impact on their care and outcome,” says Nancy Rodig, MD, medical director of the Renal Transplant Program and a study co-investigator. “Furthermore, future research will expand our understanding of kidney disease and may result in improved therapies.”

Nina Mann, MD, was first author on the study, presented last fall at the American Society of Nephrology meeting. Contributing researchers were Shirlee Shril, B.Tech, MS; Daniela Braun, MD; Weizhen Tan, MD; Dervla Connaughton, Mb, Bch, BAO; Amelie T. van der Ven, PhD; Hadas Ityel, MD; Kassaundra Amann, BS; Leslie Spaneas, MPH, RN, CCRP; and Michael Somers, MD. Transplant surgeons Khashayar Vakili, MD and Heung Bae Kim, MD, were also co-authors.